Have you ever paced up and down a rack of bicycles trying to remember where you locked yours up at? The Acousto Optical Lock is a steel ripe style cable lock that sends out an audio signal and lights up when you press a key fob. Great idea!

Have you ever paced up and down a rack of bicycles trying to remember where you locked yours up at? The Acousto Optical Lock is a steel ripe style cable lock that sends out an audio signal and lights up when you press a key fob. Great idea!

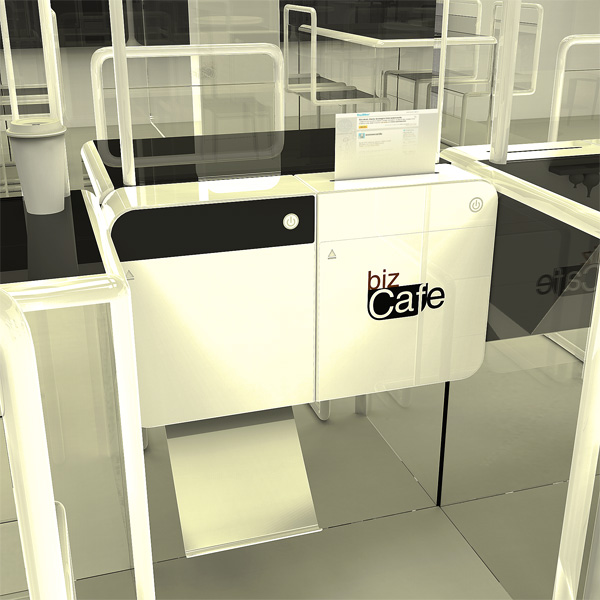

I’m embarrassed to admit it but I was one of the first people to criticize the concept of cyber cafés and even bet they wouldn’t last. To cut the story short, I had to swallow my words and I’m here to make amends. What we have here is the Biz Café – a concept targeted towards the jet-set workaholics who need gadget ready environments even while relaxing with a cup of coffee. Think about it, most restaurants and glitzy places in town have access to our social profile and instantly ping the world with a status update! So yes, in the future we will need a semi-office environment, even in cafés, so that we don’t lose out on work!

Designers: Youri Hong, Moonhwan Park & Hyoshin Kim [SADI]

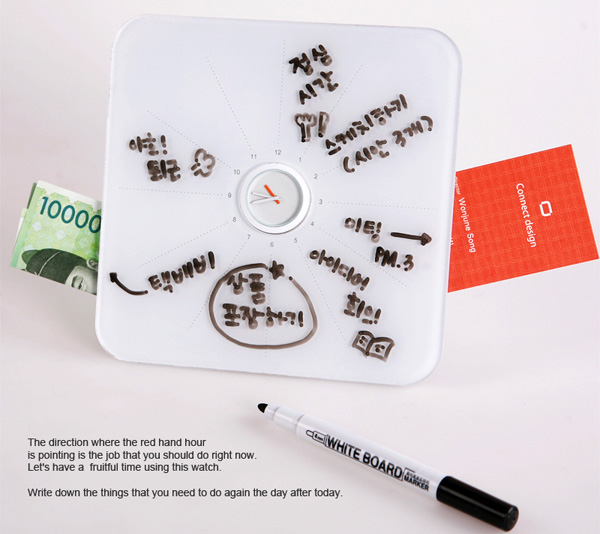

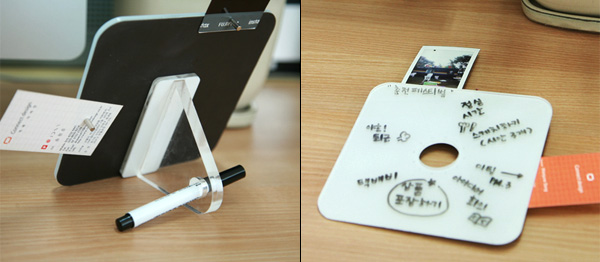

Here are some simple and neat concepts from South Korean design collective Monocomplex:

The Free Form Ruler is a measuring device that works like a pencil. The simple idea is that you'd drag the sensor tip along whatever curve or line you need the length of and the numbers are displayed via LED. Rotating the dial lets you choose the unit of measurement or reset it.

The Clip USB is a flash drive that you'll always have on hand and hopefully be less likely to lose, as it clips to your clothing.

The 2Face is a pair of eyeglasses whose color can quickly be changed by "flipping" the frames.

Dig their stuff? See more here.

Jane Atfield

Sebastian Bergne

Adam Brinkworth

Konstantin Grcic

Thomas Heatherwick

Victoria Jessen-Pike

David Keech

Wakako Kishimoto

Tom Lloyd

Kevin McCullagh

Corin Mellor

Peter Naumann

Ben Panayi

Luke Pearson

Sonya Winner

The THEN-NOW Show is an exhibition of 15 designers who were originally amongst the graduates selected by Zeev Aram to take part in the Aram Design’s Annual Graduate Shows in the late 1980s and early 1990s. This exhibition revisits the work of these designers to show the development of their career over the last 20 years or so. Their work will be represented by their designs at graduation, THEN, alongside recent work, NOW.

Zeev Aram opened his first store on London’s Kings Road, Chelsea, in 1964 at a time when there was very little in the way of modern furniture on the market. He had a real passion for design and was the first to introduce the works of designers such as Carlo Scarpa, A & P.G. Castiglioni, Marcel Breuer, Le Corbusier and V. Magistretti to the UK market. These were truly radical designs at the time and it may have seemed a gamble to show these works as part of a commercial venture. Aram however, believed that here were pieces that were important, beautifully designed and well manufactured that would stand the test of time. And so they have.

As the years went on, Aram noted that there was very little in the UK in the way of support for emerging designers and there was a real gap between designers and manufacturers. So he decided to host a yearly exhibition that would act as a platform for young graduates to show their innovative designs to the public, but principally to INDUSTRY. The exhibition was an attempt to bridge the gap and form a dialogue between a young generation of designers and manufacturers: a platform for engaging with creative ideas. This became the raison d’être for the Aram Graduate Shows.

Each year, Aram would spend the summers on the road, visiting end of year shows at over forty/fifty design colleges around the UK. The works he selected came from all creative disciplines: graphics, fashion, product/industrial design. There was no limit neither in the breadth of the disciplines nor in the quantity of designs. What mattered most was that the designs to be shown would represent the thinking of the young design graduates and their innovative solutions.

Each year there were between 70 and 90 participants, sometimes even more. The exhibitions would take over the entire Showroom for nearly a month with students and their colleges helping to mount these large shows. There was no charge made by Aram neither to students nor to colleges for participation in these exhibitions.

While looking through his archives recently, Aram noticed that many of the graduates whose work he showed are now established and well respected names in the design field. As a result, The THEN-NOW Show was born.

The main objective of this exhibition is to show to the public, undergraduate designers and designers in their early careers the progress these 15 designers have made over the last two decades.

For press enquiries please contact Anna Meyer at Origin Communications on +44 (0)20 7729 0007 or by email at anna@originuk.com.

Graphic Design by Studio EMMI

Keep updated here:

Recent events around the world expose the heightened uncertainties of a growing demand for materials that are both precious and in limited supply.

With China exporting as much as 96 percent of the world's supply of rare earth metals, the country's drastic reduction in exports sent ripples around the world. Simultaneously, governments such as the United States continue to subsidize biomass for energy, causing domestic shortages and the need to import biomass from other countries.

These trends are particularly disconcerting when viewed in the context of increased use of incineration to create fuel. The practice of incinerating waste for energy, though efficient in the short term, exacerbates the issue of materials shortages. When burning waste for fuel, many valuable and recoverable materials are lost through the smokestack that could otherwise be re-used within new product life cycles.

As governments respond to these materials shortages and imbalances by promoting conventional materials supply strategies such as increased domestic drilling, stockpiling and diversification of supply sources, there is an urgent need to call into question the basic assumption of nature's limitless supply and to deliver innovative approaches to materials management.

In this conversation with Maren Maier of Catalyst Design Review and Allan Chochinov, Editor-in-Chief of Core77.com, Dr. Michael Braungart, along with the EPEA research team encourages designers to more fully understand material flows and learn how to capture material assets at every part of the life cycle. Design can pioneer the next revolution in business, but it will need to reframe old assumptions and shape desire to the contours of a real and living world.

How can designers shape desire for a new materiality based on the real limits of our real world?

Dr. Braungart: Well, first, the business community does not have enough respect for designers. They are currently at the bottom of the management food chain. Marketing tells them what to do. That doesn't make any sense.

Designers hold a key to the future, but designers need to understand their role differently and learn to have more self-esteem, ambition and responsibility. For example, why are designers designing desire for toys made of materials that contain dozens of chemicals? Why are designers designing desire for electronics that use our increasingly limited supply of rare minerals?

The role of design does seem to be shifting in business though. There is a perception here in the United States that designers have more of a seat at the table now and are being recognized for their strategic abilities. What is your feeling about this? How do relationships between designers, scientists, business managers and even regulators need to be redefined?

We are beginning to understand that everybody is a designer, because design is the first signal of human intention. The question is: What is the role of the design professional and what are the responsibilities of that role? I believe that design needs to intend, at the beginning, to be good instead of less bad. If design does not do that, we will need more and more legislation just to limit the amount of poison we put in the air or in the water. But legislation is really a sign of design failure.

Designers must consider the consequences of their choice of materials. This is not complex. As scientists, we can alert them to the consequences. We can tell them what happens when certain materials go into the environment. I see myself as the 'material boy,' as Madonna would say, for designers. They simply need to say, "I want to use that material, what is the consequence of that?"

Designers often think they are in the artifact business, but as you say, they are in the consequence business. It is said that 90 percent of a product's consequence is determined in the first 10 percent of the design process. How can designers apprentice themselves to change their way of thinking?

Designers must learn to expand their interests and responsibility beyond just aesthetics. I see it slowly happening. For example, in Japan, the designer truly understands the link between total quality and total beauty. It's not beautiful if it is connected to child labor. It's not beautiful if it poisons the oceans. It's not beautiful if it perpetuates conflicts over precious resources. It's not about only the right materials. There is also a social component. Clearly, there is an opportunity for designers to become pivotal players in the industrial transformation, adding immense strategic value.

Regarding strategy, can you talk about the designer's opportunity in the context of current rare minerals shortages and trade disputes with China? Governments in Europe and the United States mainly highlight traditional solutions such as opening up domestic mining, finding new ways of extraction, stockpiling, etc. You rarely hear about design for recycling or innovative approaches to materials management. How could the designer in this case add strategic value?

It's amazing that people think these are viable long-term solutions. These elements are not endless and we certainly don't have enough meteorites landing on Earth to increase the availability of some strategic materials. What it tells us is people need a new understanding about materials. With the exception of two or three elements, there are other areas that can be mined for rare earth metals outside of China but it hasn't been done because it has always been cheaper to get the metals from China. And that is a big strategic mistake. We need strategies to recover the materials differently or new strategies to design different products.

And it is changing. For example, we have worked with Phillips to jointly design a new TV set that doesn't contain any rare elements. We designed them out.

I was just reading about Pixel Q's new screen debuting at CES. Another example is Mary Lou Jepsen, who designed the One Laptop Per Child screen, which is incredibly energy saving.

That's right. These are all examples that show how we can and need to put more quality criteria in the design at the beginning. Design can't be just about recycling. It needs to be about upcycling, because we need to use the intelligence of products for a new purpose. This can only be done through a comprehensive strategy around biological and technical nutrient flows.

Right now, for example, we are working on glues in a new design paradigm. These glues can be eaten up by enzymes, so that after five years you can put your glues in an enzyme bath and it falls apart because the enzymes eat the glues. Then the components can be used for other things. We are also working with a Japanese company on glues that shrink when you heat them up. You can define at what temperature the product will fall apart. This is an important innovation. We no longer need to have children in China with a hammer taking out some of the toxic or rare materials. This is an example of good design thinking from the beginning.

How would you suggest designers begin to approach biological and technical nutrient flows into their design strategies?

First and foremost, remember that recovery of manufactured materials is preferable to destruction. By turning waste into food and feeding two fundamental industrial metabolisms -- the organic or technical -- companies can continually and effectively re-use materials in closed loop systems.

If this is to be successful, however, the entire system must work together, from manufacturing to incineration. In some cases, for instance, incineration cannot be avoided. It is important to modify the conventional approach to incineration and create precise definitions for the types of materials that can best be used for burning. Incineration can be considered from a Cradle to Cradle viewpoint only if clean-burning man-made materials or biomass are combusted after a defined use "cascade," with high value energy generation and production of beneficial ashes.

Can you elaborate on the concept of a cascade?

A cascade describes the consecutive use of materials in products of lesser and lesser properties until at the end, the process results in destruction or re-production of the material. At the end of that cascade the nutrients in biological materials are returned to the soil to support biodiversity and continued soil productivity. Throughout the cascade, products are designed for the biological cycle, including energy recovery and CO2 storage and are free of harmful contaminants. In the end, the remaining incinerated materials are clean-burning and produce beneficial ashes.

If we take this approach with paper production, for instance, within three years we could create paper that flows into natural biological cycles, leaving only a positive impact on the environment. Not only is this an eco-effective use of materials flows, it creates economic value. For example, the pulp and paper industry did a study showing the paper cascade produces up to ten times more economic benefits than burning virgin biomass.

As you can see, designers have an immense responsibility to create a material stream that allows for recovery of materials and an intelligent use of incineration.

In your work with companies such as Philips, what have been some of the challenges of integrating these Cradle to Cradle concepts into company strategies? What are of some of the roadblocks you have faced?

The key obstacle in companies has been the conversation around eco-efficiency. People have been optimizing the wrong things. Many of the current issues with shortages result in part from a decades-long strategy of outsourcing. Outsourcing has become such a religion that governments have nearly forgotten the value of materials to their strategic interests, and "just in time" inventory has become "just out of materials." The Cradle to Cradle framework shows how companies can solve their strategic materials issues by promoting eco-effective materials management design strategies in-house.

To do so, we need to redefine sustainability so that it defines what it means to make good design rather than design that is less bad. The whole sustainability conversation around 'footprints' is a challenge as well, because the message to the customer is, "You can minimize your footprint even more if you don't buy my product," which is hardly economically viable.

So in some ways, we have created a misguided message about sustainability. Do you believe our relationship with nature is focused too heavily on conservation and limitation?

The first thing we must do is celebrate the human footprint. We can learn from nature, but it's a partnership, not a romantic relationship. We can learn from the Dutch who never romanticize nature. If you talk about Mother Nature, they would frown because most of the country is below sea-level and the next flood could take them. The key is to learn not to romanticize nature. We are romanticizing nature because we have been torturing it so much. A human footprint need not damage either the environment or human health. Good design can create positive flows.

From country to country, there seems to be cultural influences at work as well. How does culture play a role in designing within the Cradle to Cradle framework, particularly here in America?

Definitely the social and cultural aspects are far more exciting than the technical and material aspects. In some ways, the technical and material aspects are only mining the social and cultural deficits. Take Americans: because the culture has so many taboos around sexuality, it makes sex far more relevant. It permeates the language. Think of 'joy sticks' for video games, or 'virgin' raw materials as just a few examples.

Also Americans have about five times more "one way" products than we do in Europe, because they can't use something that has been used or touched or tainted by somebody else. So in a lot of ways, the cultural undertones don't really allow recycling.

Community design is key and that is why the designer must play a much more important role. That is why we need new strategies that work within cultures.

There are lots of stories about neighbors complaining about their neighbors hanging out laundry to dry because they don't want to look at drying lines, or communities complaining about windmill farms ruining their views. So in many ways, it is not just regulatory limitations keeping people from being reasonable. It really is also cultural and behavioral. Enzio Mancini once said, "you can't offer somebody the same but less. You have to offer them different."

That is quite correct. That is why Cradle to Cradle is not about telling people how they should be. We like how they are. In Cradle to Cradle, there is no should, have and must. We want to support people how they are. If the culture in the United States is based on these subliminal sexual taboos, it's ok. We don't want to tell them how they should be. We have to celebrate diversity. It's not one size fits all anymore.

Your philosophy is both inspirational and aspirational, and clearly implementation requires incremental steps. I'm curious about your plans for Cradle to Cradle certification in the United States, particularly in light of the new non-profit Green Products Innovation Institute (GPII) you recently founded in California?

Please make sure there is no misunderstanding, certification is the opposite of Cradle to Cradle. Certification says, "I feel bad and have to come back every two years to find out if you still feel bad." But in a fear society, like in the UK, in Germany, in the United States, it needs it -- it's a transitional chain. The only way certification can be replaced is by being transparent about what you are doing and by making sure that the ones making profit take the risk as well.

If a business owns 4,360 chemicals it is not ok to advertise only the benefit and socialize the risk. The business needs to make transparent what it is doing. It needs to say that: if it gets consumed, it is designed for biological nutrients. The business has the responsibility and the liability for it as well. But if it's a technical nutrient, the business needs to make sure it stays in the technosphere and it doesn't need to certify anything.

And yet you need to explore certification, because it is the most important tactic in this culture.

Yes, but you can only certify the past. You cannot certify the future. And I am talking about the future. I can certify control, but I cannot certify support. I can't emphasize enough how important it is to get enough young, talented designers to lead the charge and to engage people in other disciplines and begin a positive dialogue. If you think about it, there are few ways to control people to do less bad, but there are millions of ways for design to support people being good. What I have learned is that people are only greedy out of fear. They are always friendly and generous when they feel accepted and supported.

Surely, this is something we all desire. And designers certainly have the ability to shape design strategies around those positive goals.

Yes. It is just a question of time, and it is a question of the vitality of the system. We need to make sure we have a new kind of industry in place. We only have about ten to fifteen years, because the system has already started destroying itself. We need a revolutionary change and the only way this will happen is with people like you, which is why I am so thankful to talk to you. We need designers to understand, have fun with the idea of designing around positive goals and communicate those goals.

STRATEGY IN ACTION Organizations can take these steps toward more effective materials management processesDesign with manufactured materials that can be recovered for upcycling

If incineration cannot be avoided, use it effectively. First consider rapid oxidation burning options where nutrient recovery can be more effective.

Design with materials that areclean burning (i.e., without harmful emissions)

Use materials destined for eventual incineration first in a cascade. Combustion is the last step of the cascade prior to reuse of ash.

GP II, new certification non-profit for Cradle to Cradle:http://www.c2ccertified.org

Dr. Braungart is also the scientific director of Environmental Protection and Encouragement Agency (EPEA) Internationale Umweltforschung GmbH, of Hamburg, Germany, founded in 1987. He holds a professorship at the Dutch Research Institute for Transitions (DRIFT) at Erasmus University of Rotterdam in collaboration with the Delft University of Technology (TU Delft) and is professor of Process Engineering and director of the interdisciplinary materials flow management masters program at Universität Lüneburg in Germany. Additionally, he is co-founder of the Hamburg Environmental Institute, established in 1989. He continues to lecture at universities and consult with companies and organizations around the world.

Environmental Protection and Encouragement Agency (EPEA Interational)

Co-authors

Douglas Mulhall, Rachel Platin, Sonja Rickert-Kruglov,

Tanja Scheelhaase, Christoph Semisch, Christian Sinn, Yael Steinberg.

Last month we mentioned Open Source Ecology's Global Village Construction Set, an extremely ambitious project to bring industrial tools to areas that cannot afford them. We were thrilled to learn they've beenselected as a Semi-Finalist in the Buckminster Fuller Challenge.

To refresh your memory, the GVCS team has narrowed down thousands of industrial machines and initially determined that a society "with modern comforts" can be built with 40 different machines. (It's been upgraded to 50 since our original post on them.) They then began designing prototypes of these machines, using an open-source methodology which led them to discover they could produce the machines at just 1/8th the cost of what they'd go for if purchased directly from a supplier. Also helping to keep the costs down is the Lego factor, whereby as many interchangeable parts, modules and motors as possible are integrated into the designs.

Obviously they're not looking to build car factory paint-spraying machines, but things that are more practical. Their Compressed Earth Brick Press machine, for instance, is designed for users to dump local dirt into a hopper at the top, and it then spits bricks out of the bottom at a rate of 16 per minute. Other machines in the pipeline are a sawmill, an induction furnace, a steam generator and a backhoe.

We love the ethos of Open Source Ecology founder Marcin Jakubowski:

I am a boundary-crossing iconoclast who believes that material well-being should not be a privilege that only the few can enjoy. I believe that the necessity 'to make a living' should not be an underlying force in civilization that prevents people from pursuing their true passions. I am convinced that by injecting a little wisdom into our technology, we can tame technology for true human service. I believe that open society and open source economic development is a route to abundance and prosperity for all.I am convinced that until we learn to share, there will not be enough for everybody. Sharing means engaging in open source economic development. Open source economic development is an economic paradigm where everybody has access to best practices, optimized product designs, and access to local production. I believe that one day, open access to the means of economic production may become a favored option over monopoly money - and stimulate much higher levels of innovation that are currently possible....

In this second video, Marcin explains what gave him the idea for the project in the first place:

4 Years of Factor e Farm in 4 Minutes from Open Source Ecology onVimeo.

Đây là năm thứ 32 của Bangkok Motor Show, được tổ chức tại địa điểm mới - Khu Challenger của trung tâm triển lãm Impact, Muang Thong Thani, Bangkok. Trước đây, sự kiện này diễn ra ở Trung tâm triển lãm và thương mại quốc tế

Trong những mẫu xe mới được trông đợi nhất tại Triển lãm ô tô Bangkok năm nay có Honda Brio, Ford Ranger và Chevrolet Colorado thế hệ mới... Hãy cùng điểm qua:

Tâm điểm của Honda tại Triển lãm ô tô Bangkok 2011 đang diễn ra ở Thái Lan là Honda Brio, mẫu xe được phát triển riêng cho thị trường châu Á, cạnh tranh với Hyundai i10, Kia Morning (Picanto), Nissan March, và Suzuki Alto. (Ảnh: Top Gear)

Được thiết kế và phát triển tại Australia, xe Ranger thế hệ mới nằm trong chiến lược sản phẩm toàn cầu One Ford, và Thái Lan, thị trường xe bán tải lớn thứ hai thế giới, sẽ là một trong 3 trung tâm sản xuất toàn cầu của mẫu xe này. (Ảnh: Paultan)

… hay Wiesmann Roadster MF5 (Ảnh: Top Gear)

… hay Proton Lekir. (Ảnh: Top Gear)

... Mazda3 (Ảnh: Top Gear)

... hay Skoda Yeti (Ảnh: Top Gear)

Cùng với cản dưới thể thao, bộ 3 đèn trước tạo cho mũi xe diện mạo mới.(Ảnh: Paultan)

Tại triển lãm có rất nhiều gian giới thiệu các trang thiết bị giải trí công nghệ cao dành cho các tín đồ tốc độ. Như ảnh trên là gian Mercedes-Benz PlayStation 3 Gran Turismo 5 (Ảnh: Top Gear)

Lãnh đạo Ford say sưa đua xe mô hình trên đường xoi rãnh (Ảnh: Flickr/Ford)

Mô hình xe Mercedes-Benz đầu tiên, ra đời cách đây 125 năm (Ảnh: Bangkok Post)

Những chiếc xe Morgan cổ (Ảnh: Bangkok Post)

Xe Chevrolet cổ (Ảnh: Bangkok Post)

Chiếc xe bán tải Chevrolet Brasil đời 1960 (Ảnh: Bangkok Post)

Với chủ đề “Khám phá, bước cải tiến mới”, triển lãm năm nay dự kiến thu hút hơn 1,6 triệu lượt khách thăm quan.

Pro-ID Design by Topwpthemes. Converted By Ha Nam Son , Email: pro.idgroup.vn@gmail.com Or swin9986@gmail.com .