26/2/11

Reflections on LIFT Conference 2011

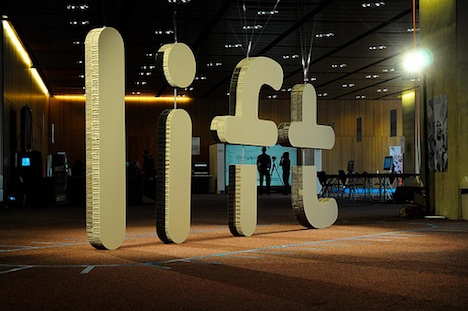

A few weeks ago I was, together with about 1000 other people, in Geneva, Switzerland, to attend the 2011 LIFT conference.

LIFT is really a series of events, launched in 2006 and now taking place in France, Korea and Switzerland, built around a community of pioneers who get together to explore the social implications of new technologies. The LIFT conferences are driven by a dynamic and informal team of people whose public faces, Laurent Haug and Nicolas Nova, are quite well known in the user experience community.

The main event is the acclaimed three-day yearly conference in Geneva (now in its 6th edition) and this year the theme was: What can the future do for you?

Writing about a design and technology conference has changed a lot recently -- especially when that conference streams all sessions immediately and Twitter comments have become pervasive.

So I chose to wait a bit, look back at some of the videos (they are all online here), let it all sink in and look back in reflection.

My angle is personal of course, but it struck me that there were a number of core themes that drove a substantial part of the discourse at this year's LIFT. They are also, I think, the main challenges we as experience and interaction designers will need to address: networks, identity, people and openness, and algorithms.

NETWORKS

Today we are vividly witnessing the fact that revolutions don't get made by leaders anymore. And this is illustrative of a larger social paradigm shift in our society, argued Don Tapscott, author of the 2006 bestsellerWikinomics, How Mass Collaboration Changes Everything, in his keynote presentation. Social media has lowered transaction and collaboration costs and enhanced people's capability to collaborate. Hierarchical leadership models are becoming more and more outdated, stalled and failing. The Industrial Age and its institutions have run out of gas. In short, Tapscott says, we are facing nothing less than a turning point in human history, and this creates friction, of course. The huge challenge for us now is to shape this emerging open network paradigm which, to many in charge, seems to lack structure and organization. There is no easy answer in how our societies and businesses can deal with the challenge of rebuilding themselves along this new model of networked intelligence. We do know the principles though -- collaboration, openness, sharing, interdependence and integrity, and you may want to see the presentation or read Tapscott's new book Macrowikinomics: Rebooting Business and the World to understand how these principles are currently starting to be applied in business and government.

Confronting the same theme was Ben Hammersley, Editor at Large forWired UK. Thirty years younger than Tapscott, his different take on networks is quite refreshing. In essence both speakers addressed their own generations: Tapscott the digital immigrants who come from a hierarchical world and Hammersley the in-between "buffer" generation who constantly have to deal with the older, somewhat "bewildered" generations, the political, industrial and intellectual elites, that currently hold the levers of power.

Hammersley focused on the psychology behind it all -- the dominant intellectual framework of the 20th century now gets inverted into a new model, the network model, which has to deal and co-live with the older hierarchical model. People from these other generations might have, what he calls, the "wrong cognitive toolkits" to function well in a drastically changing world. Hammersley explained what it means for the older generations to be "weirded out by modern times" and why there has been so much focus recently in the world of major corporations and institutions on "innovation" and "thinking outside the box". It is, he says, a sort of therapy in a world where many hierarchies no longer make any sense. Our primary problem (and he is referring to his own generation) is not to encourage innovation, but to translate it. Our job is to clear the path to allow the young people to come through with their new ideas.

These questions were exactly the kind of stimulation that got the highly active mind of Brian Solis (personal site) going. Soiis, a US futurist, simply loves to put his teeth into anything related to reputation, trust, social capital and influence. We each lead three lives in the real world, he says: a public life, a private life and a secret life. Online however, we are all guilty of blurring the line between the three. We are all over-sharing. We are all indexed, ranked and scored by a great variety of online services. Yet, none of the services currently out there, is actually measuring your reputation, your influence. What they are doing is measuring the semblance of your social capital: what you are worth within these social networks, essentially becoming a credit score for the social web. We are measured by what we say and the company we keep. This social graph is already being used by (US) credit card companies to determine their potential risk. Knowing that, how do we become more mindful in how we use social networks?

Solis cited political scientist Robert Putnam who defined social capital as "the collective value of all 'social networks' and the inclinations that arise from these networks to do things for each other." Social capital, Putnam said, can be measured by the amount of trust and "reciprocity" in a community or between individuals. Nothing of that, however, is measured by today's tools. The problem is that these imperfect "social capital" scores are currently used against us.

Now, asks Solis, let's look at the issue from a people's perspective: What do we, as people, expect to get in return for our investment in social networks? It breaks down to trust, relationships, reciprocity, authority, popularity and recognition.

At the moment, the currency of social capital is the social object: the thing that you create, do or say online. When you publish it, it has an effect and that effect is measured. The problem is that we are being measured differently in every network. Moreover, context is missing most of the time, and the difference between social currency/capital and influence is not addressed. Influence is the capacity to trigger an effect. It is an ability. We do know that the elements of digital influence centre around a great many terms such as trust, authority, reputation, reach and social capital, but we don't know how they connect. Today there is just a great deal of confusion (and Solis promised a paper to clarify it all). Knowing how things currently work, Solis has definitely become more mindful in sharing online and in fact he shares less now.

But Solis ends on a positive note: giving back is the new black. Businesses that give something to their customers (advice, ideas, suggestions, tools) earn reputation and influence.

On the very last day of the conference, the most powerful statement about identity came from an artist.

In 2002, Hasan Elahi, a US citizen, somehow ended up, wrongly of course, on a US terrorist watch list and was extensively questioned at Detroit Airport. He was released but had to endure many months of "interviews" with FBI officials and he had to defend himself through no less than nine successive lie detector test. Unfortunately he couldn't be formally cleared because he was never formally charged. Not surprisingly, Elahi was concerned (and somewhat scared) that similar things, or worse, would continue to happen to him after any successive trip abroad. So initially he called the FBI to share his travel plans with them. This soon changed to emails and then eventually became a very extensive and highly automized website he created in 2002 that basically tracked his life. At first the site was private but in 2003 he decided to make it public -- assuming that safety is also in the numbers.

Elahi was initially considered somewhat of a creep by his friends to go to the extremity of making his life public. The real irony and the very heart of his speech is that now, seven years later, there are half a billion people doing essentially the same thing every time they update their Facebook status.

Interestingly, Elahi said that by giving out so much information about himself, he actually leads a rather private and anonymous life. He generates so much data but to understand them you would still have to do the analysis, and when you do that, you get very little in return. All of us are generating data now.

So his FBI encounter resulted in a very extensive real-life project about identity management. Having a little bit of information about you is very dangerous, Elahi says, but by having a large amount of information you get a better picture. By generating a lot of information, you become in control of your own identity, rather than someone else defining your identity.

Steve Portigal of Portigal Consulting focused on the importance of understanding people in order to create innovation.

In a condensed and highly practical session, Portigal explained the power of the participatory or user-centered design process. What is the meaning behind what people do, asks Portigal. By focusing on gathering meaning, we can synthesize and find connections that no one connected before. These connections can then be used to create stories that can be applied in the design process to make change happen.

What makes Portigal's talk relevant is that he explains how concentrating on understanding people's behavior is so much broader than asking people what needs they have and what they would like as some still seem to think. This approach can lead to misjudging the power of user-centered design in innovation. People, says Portigal, are not good at talking about solutions, but we can understand a great deal about needs by observing people. By leaping away from the specific, we can get at the principles that drive the specific. So the question that drives the research is not the solution but the problem we are trying to solve. Contemporary user-centred design, says Portigal, implies a willingness to shift what we think the problem is, a willingness to shift what we think the solution is, and a willingness to be comfortable with ambiguity.

Nick Coates elaborated this people strategy into the methodology of co-creation, first describing the methodology and then giving a great case study on how he used co-creation to design the cabin space for Etihad Airways.

People was also the topic of Thomas Sutton of frog design Milan, approached from his vision on open innovation.

Sutton's focus is on contextual networks and the way changing meaning within those contexts create changing behaviors. Sutton gave an interesting perspective on how content and service providers would start on platforms (like Microsoft, Apple and Sun), whereas more recently they actually start from digital and physical touchpoints (like Amazon, Twitter). Through a strategy of openness providers then moved from these outer touchpoints to the layer of platform. Twitter has nearly become a platform.

This has big implications for design. End-users are starting to move very opportunistically from touchpoint to touchpoint, and this undermines some of the basic tenants of classical interaction design: the idea of understanding and designing an ideal path for your user. People are now creating their own opportunistic ideal paths based on the forms of access that they have available to them at any one time. So designing an ideal path has become pointless. The most rewarding strategy is to allow an open flow between channels and platforms by designing an experiential thread to them all. This means that designers have to design for connectivity (giving people the space to innovate for themselves), and Sutton presented some of the participatory tools frog design uses to achieve exactly that.

In today's financial markets, everything is electronic and it is important to hide transactions wherever possible (since you don't want to show your intentions or strategies). If you need to move one million shares, it is better to move 10,000 individual lots of 100 shares, much like how Stealth bombers make the enemy believe that what flys in the sky isn't a plane but simply a lot of little things, like birds. That's why banks use algorithms and have become very equipped at making these appear as random as possible. 70% of all trades in Wall Street are either driven by an algorithm trying to appear invisible or another algorithm trying to find that invisible algorithm.

Today, algorithms do not just impact our pension funds but also affect a much broader part of society. Algorithmic effects are applied to determine what we hear and how those songs are made, what they sound like, what we watch, what we are going to see in the movies, what we read (the titles of what we read are algorithmically evaluated and determined), who we are matched with if we go online to get matched with somebody, what we call news, who gets arrested, what we drive, how we get there, what we eat and even what we drink.

There are, says Slavin, three problems with this: opacity, inscrutability and "something darker and harder to describe" -- the idea that taste could algorithmically be determined. Millions of dollars could be moved by that. What if an algorithm would focus not on what movies you might like (as is already the case), but what movies should be made that you might like (as is also starting to become the case)? In a way, it is regression in the sense that it regresses towards the mean. In doing so, we are producing a kind of monoculture and we lose the tools to understand how it actually works (even though we wrote the algorithms).

Now and then algorithms cause crashes. Serious crashes. And since algorithms are now everywhere, we need to ask ourselves, what does a flash cash look like in the wine industry? In the criminal justice system?

No Response to "Reflections on LIFT Conference 2011"

Leave A Reply